How Computers Store Data in Memory: Brief Intro

Introduction

When we communicate with each other, we use complex natural languages like English, Portuguese, or Russian. The language we use depends on our location or the community around us. When we see something, we perceive information visually through our eyes and brain. And when we count numbers, most people are familiar with one system — the decimal system, where each position can be represented by one of 10 digits: 0, 1, 2, ..., 9. So, at least three independent ways exist to perceive and exchange information.

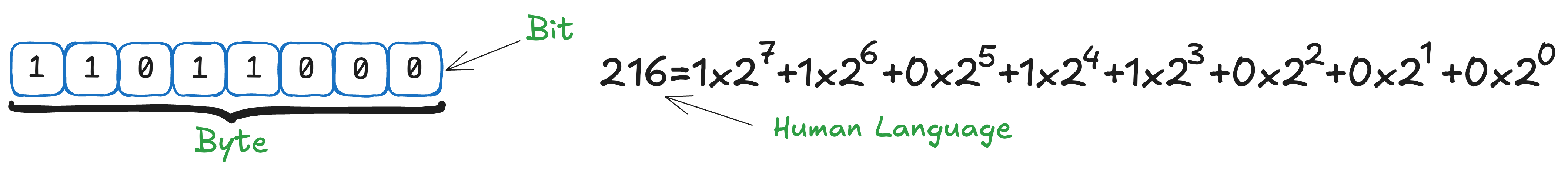

Computers, however, operate very differently — and in some sense, much more simply. They do not have a native natural language or vision system at their core. Instead, they use only the binary system, composed of 0 and 1. Each “box” of information can contain either a 0 or a 1, and this unit is called a bit. Historically, 8 bits make up a byte.

Higher-level constructs, such as Natural Language Models (LLaMA, ChatGPT, Grok, etc.) and Vision Systems (YOLO, Faster R-CNN, Stable Diffusion, etc.), are built on top of this fundamental binary representation.

Understanding how computers “speak” at the basic level is critical for building intuition in Deep Learning. In this post, I learn how computers represent and store information, how it connects to data types, and why these foundations matter when designing and optimizing AI models.

Decimal vs Binary

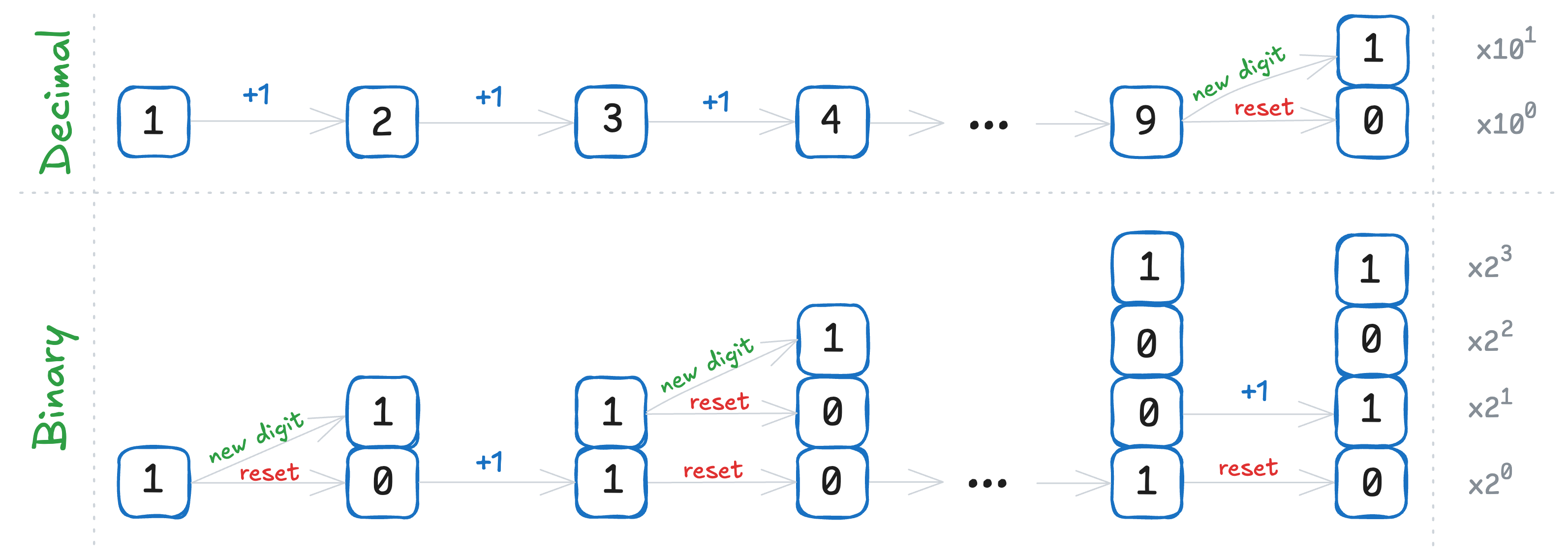

The decimal system is the numeral system we use in daily life. Each digit can take one of 10 different values: 0, 1, 2, ..., 9, ordered naturally from smallest to largest. To construct numbers, we use powers of 10: when increasing past 9, we reset the digit to 0 and add 1 to the next higher place value. The binary system works similarly — but instead of 10 possible values, each digit (bit) can only be 0 or 1. Here, the base is 2, and each digit represents a power of 2.

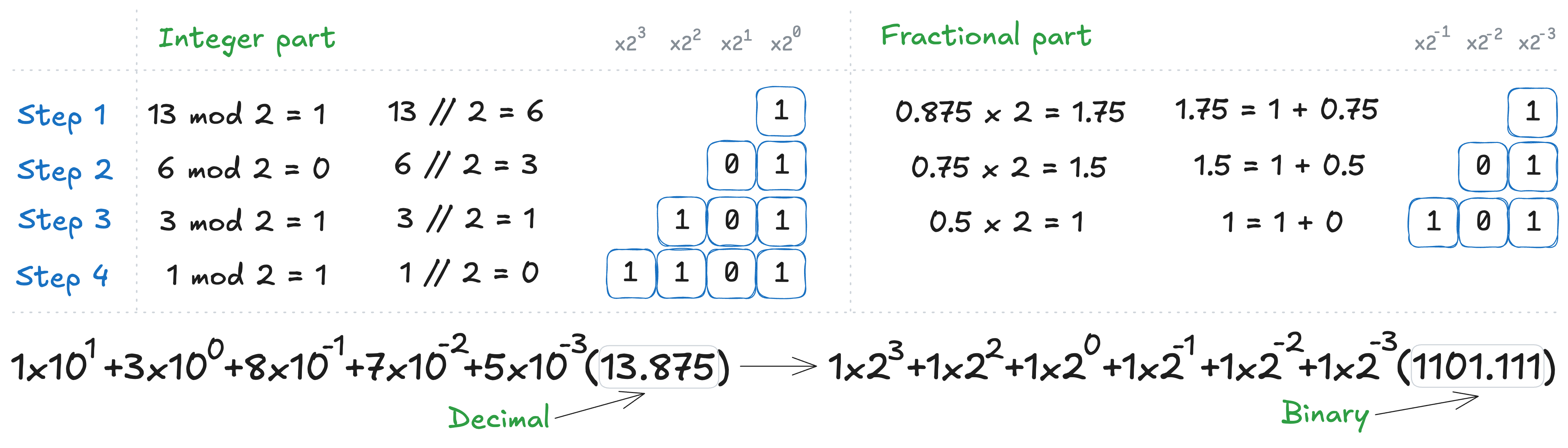

Fractional numbers follow the same idea: each digit after the floating point represents a negative power of the base - 10 for decimal numbers, and 2 for binary numbers. The algorithm for converting a fractional number from decimal to binary is iterative and slightly different for the integer and fractional parts:

- For the integer part, divide the number by 2, record the remainder (0 or 1), and continue dividing the quotient by 2 until it becomes 0.

- For the fractional part, multiply the fraction by 2, record the integer part (0 or 1), and repeat the process with the remaining fractional part. The process stops when the fraction becomes 0 or when the desired precision is reached.

Below is the step-by-step calculation for the number 13.875:

We’re used to the decimal system; however, the binary system follows the exact same logic — just with 2 symbols instead of 10. Inside a computer, tiny transistors act as switches that can be either ON or OFF, determined by voltage levels. It’s much easier and more reliable to distinguish just two states — high vs. low voltage — than to detect multiple. This simplicity and robustness is why all information in computers is stored in binary.

Main Data Types

At the core of computing, we work with a few basic types:

- Integer (

int): Whole numbers like-17,0,256, etc. - Floating-point (

float): Numbers with decimals, like3.1415or-0.00127. - Boolean (

bool):TrueorFalse, used in logical decisions. - Character (

char): Single characters like'a','Z','Я','+'. - String (

str): Sequences of characters like"Capybara likes cuddling".

Each type has a pre-allocated size that depends on the programming language and implementation details. For example:

-

int8(8-bit integer) has a size of 1 byte and can represent values between-128(-2^7) and127(2^7 - 1). - A regular

intin Python has a size of 28 bytes — which may seem surprisingly large. This is because Python integers include significant metadata (type, reference counts, etc.) and allocate memory dynamically.

One can check the size of an object x in Python with sys.getsizeof(x). However, it measures the full size, including Python’s internal overhead, which makes pure Python relatively inefficient for data storage and processing. To overcome this, optimized libraries like NumPy and PyTorch are used. For instance, NumPy provides fixed-size types like int8, int16, int32, etc. We can check the size of a NumPy object (e.g., x = np.int16(2)) using x.nbytes, which gives the actual payload size.

Strings are represented using bytes, interpreted according to the character encoding — the system that maps bits to characters.

ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) uses one byte per character and defines 256 symbols (128 in the original standard). For example, the string "Capybara" is be encoded in ASCII as [67, 97, 112, 121, 98, 97, 114, 97].

When more characters are needed (such as emojis, Chinese ideograms, or mathematical symbols), modern systems use Unicode, which assigns a unique code point to every character. To actually store these code points as bytes, encodings like UTF-8, UTF-16, or UTF-32 are used. In UTF-8, each character uses 1 to 4 bytes, depending on the numerical value of the Unicode code point; and UTF8 is backward compatible with ASCII. Version 16.0 of the standard defines * 154,998* characters across 168 scripts.

Understanding Unicode and encoding schemes is critical in areas like Natural Language Processing (NLP), where text from multiple languages must be handled efficiently and reliably.

Data Types Used in Deep Learning

Deep learning relies almost entirely on numerical tensors. Everything — models, inputs, outputs, intermediate activations — is stored as tensors, and most of them are floating-point based.

The most common types:

-

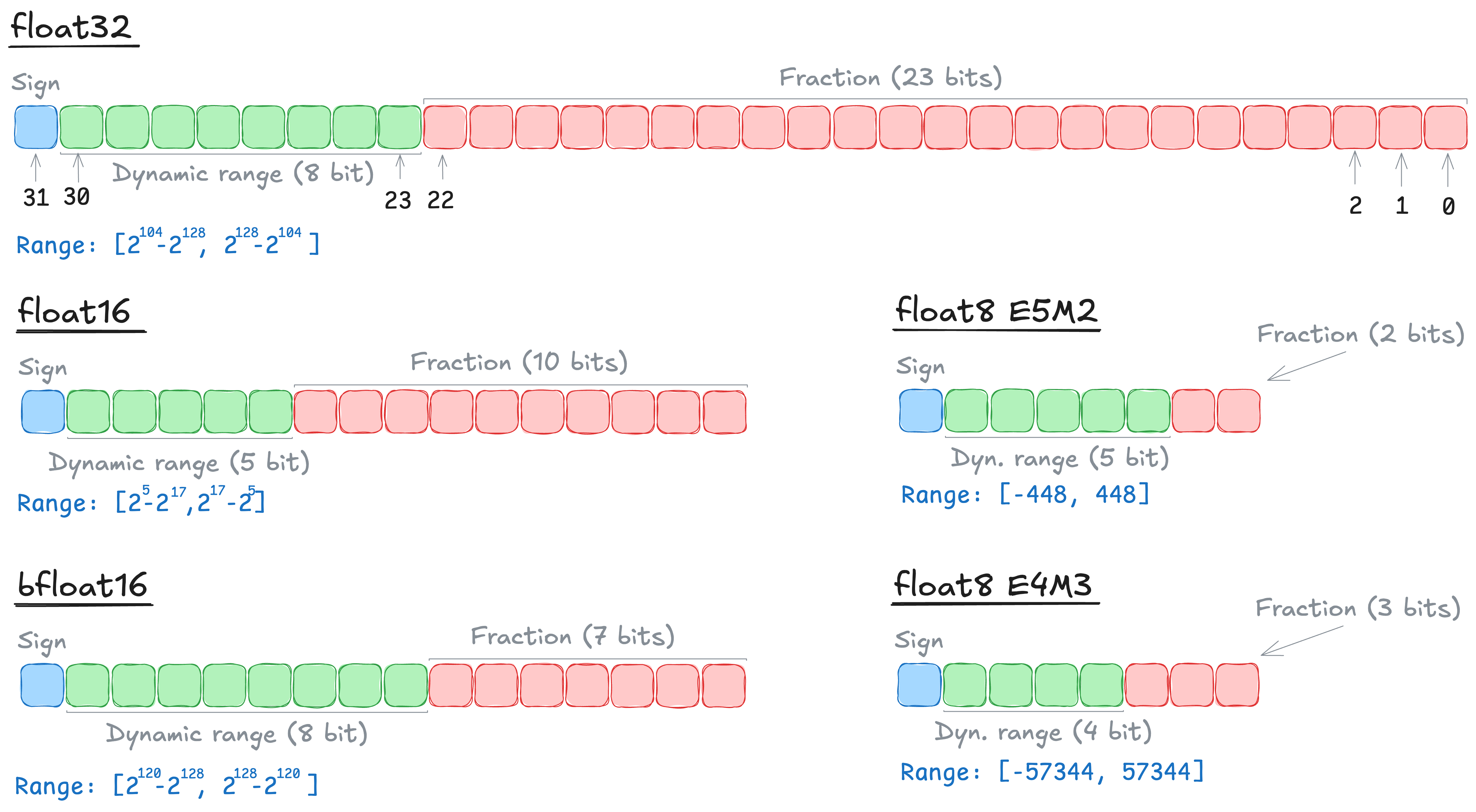

float32: Single-precision (32-bit floating point) — the default choice for most models.

Drawback: large memory usage (both GPU and RAM). -

float16: Half-precision (16-bit floating point) — used for faster computation and reduced memory footprint.

Challenge: lower dynamic range, can cause instability (overflow and underflow). Especially important for larger models. Used much less nowadays. -

bfloat16: Brain Floating Point, designed specifically for deep learning. It addresses the issue withfloat16- it keeps the larger dynamic range (the same asfloat32), but with reduced fractional precision — better for training stability with less memory. It is good enough for forward pass computations.

Challenge: for storing optimizer states and parameters, you still need to usefloat32. -

fp8: 8-bit floating point - a very recent innovation, available on NVIDIAH100GPUs.

Still experimental and not widely adopted. -

int8: 8-bit integers — used in quantized models to reduce size and speed up inference.

Floating Point Internals

Floating point formats control the following two things:

- Dynamic range: how far the binary point shifts — up to 127 positions in either direction. We subtract a bias of 127 (binary 01111111) to allow both positive and negative shifts.

- Fractional part: how finely numbers can be distinguished (handled by the mantissa bits).

For example:

-

fp8 E4M3(4 exponent bits, 3 mantissa bits) can represent numbers like11110and0.0001111(3+1 meaningful bits). -

fp8 E5M2(5 exponent bits, 2 mantissa bits) can represent111000and0.0000111(2+1 meaningful bits).

The value of float32 number is calculated as (IEEE 754):

We can also write the exponent part in binary directly (more intuitive, if we compare with decimal logic):

\[N = (-1)^{b_{31}} \times 2^{(b_{30}b_{29} \dots b_{23})-01111111} \times (1.b_{22}b_{21} \dots b_0)\]Quick Back-of-Envelope Calculation

Suppose we have a tensor x with shape (batch_size=32, channels=3, height=224, width=224), typical for an image recognition model.

How much memory would this tensor consume with different types?

-

Number of elements (

x.numel()in PyTorch):

32 × 3 × 224 × 224 = 4,816,896 -

Memory usage:

-

float32(4 bytes per value):

4,816,896 × 4 = ~ 18.4 MB -

float16(2 bytes per value):

4,816,896 × 2 = ~ 9.2 MB -

int8(1 byte per value):

4,816,896 × 1 = ~ 4.8 MB

-

Notice Changing the data type immediately halves or quarters the memory footprint.

Choosing the right type has a huge impact on model speed, memory usage, and training stability.

- Training with

float32is safe but memory-hungry. - Switching to

float16,fp8, andbfloat16saves memory and speeds up computation, but introduces training instability. - Solution: to use mixed precision — selectively combining different types to balance memory usage and training stability.

Conclusion

Understanding data types is the foundation of building efficient AI systems.

It affects not only how we design models but also how fast and how large they can be.

In future posts, I’ll dive deeper into resource accounting — covering both memory and FLOPS. For memory, I’ll go beyond inputs to include gradients, intermediate activations, and other internal components of deep learning models.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: